Space, Architectural Research and the Time of a Virus (2020)

Forty eight final year students from the undergraduate programme of the School of Environment and

Architecture (SEA) embarked on their dissertation research in May 2020. The global proliferation of COVID-19 during the preceding months had led the Indian state to frame, at multiple scales, severe policing measures to partition space. These measures effected - or at least attempted to effect - a strict quarantine for the circulation of individuals and objects. Concurrently, the harsh time of the virus also shaped conversations in India’s public sphere that intensified older readings of its society and space. These readings are situated in pathological metaphors of production, community and proximity. Over the course

of the last two years, SEA’s undergraduate dissertation programme has endeavored to open out new avenues for thinking about architectural production by drawing on critical scholarly research across the

architecture, art and social science fields that complicates such readings. But what does it mean to complicate pathological readings of society and space in the time of a virus? And what philosophical avenues and actual methodological strategies may be opened out to pursue such critical scholarship in architecture when both the researcher and field interlocutors find themselves in quarantine?

In other

words, what transgressions can architectural research make in working against the grain of visible and invisible partitions that society has built in a pandemic, and whose effects might be considered as a new normal beyond its time? These are the larger questions that loom over our heads and in our face as we engage in a discussion on the dissertations of the third cohort of SEA’s undergraduate students. Their scholarship cuts across diverse research areas: urban sensorium and mediatized environments; street and urban publics; beauty and culture in urban neighbourhoods; urban memories and elasticities, ecologies, associations and negotiations of home; claims of gendered bodies and social difference to space; interfaces of nature and society; pandemic spatialities and questions to pathological readings of the city.

01 / Urban Sensoriums

> Sense Scape: Making sense of human senses in a space - Vaishnavi Bhartia

Senses are like streams, flowing from a distant source. To an unknown end.

Senses are typically considered as separate entities that act individually yet all the senses work together in synchronization of each other to provide a cohesive experience of space. The contribution of each sense is equal in power, yet unique in character. In a space, emotive characters are induced by sensory cues. These can be visual, auditory, olfactory, environmental, or haptic cues of any nature.

Recalling some of my personal experiences such as visiting Golconde in Pondicherry was such that there was an experience in the transition of how the space transformed from a private room to a room that opened up to the corridor and then the corridor opened up to the outside. In the case of Lunuganga in Sri Lanka, when I entered a building designed by Geoffrey Bawa, it evoked a sense of pleasure that goes perfectly with the climate, culture, and landscape of Sri Lanka. A seamless transition between the landscape and the built unbuilt. Both of these experiences of transience and pleasure for me emerged on the reliance of using sight as a tool to experience these spaces.

However, I feel that these spaces get accessed and experienced differently by entities with an absence of a particular sense. The majority of our built environment is designed for people who can hear, walk, look with little regard for how the walking, talking, and hearing-impaired navigate and sense space through their different senses. For the differently-abled, the absence of one of the senses makes other senses sharper and more active, and thus the experience of space itself is a unique sensorium that I wish to interrogate in this thesis. I am exploring the possibilities of how a person without a sense of sight, senses, and experiences space through his other senses. Because of seeing, the sighted has developed a certain way of seeing, where the world is becoming more ocular centric.

To understand different senses, references that were referred to are Phenomenology of perception by Maurie Merleau Ponty, The Eyes of the Skin by Juhani Pallasmaa, and Touching the Rock- An Experience of Blindness” by John Hull helped as the main reference for this thesis. After getting some insights, for digging deeper into it, I had conversations with people with a loss of sense of sight. Through that, I got detailed insights on how space is sensed by them. The sense of smell is universally understood; however, the emotions it evokes and the memories it restores vary on an individual basis. The sense of touch often provokes a different texture which is then associated with an object. The sense of hearing provides the ability to perceive sounds and understand the surrounding. The presence and absence of these senses thus render certain densities in the experience of space.

Through their experience, I undertook the drawing of the sensory landscape. The neighborhood drawing swatches act as a base drawing for exploring the sense landscape within the space. So the base drawing is then overlapped with the sensorium drawings. The sensorium drawings then represent how a blind explores or navigates the space through his senses such as hear, smell, and touch. The drawing of the sensorium reveals the factors of the tactility of the surfaces, the movement of air, the presence of generators of smell, the idea of materiality, all of that shapes the understanding of the space. So space is not limited to walls or boundaries, space is about tactility, comfortness increases when we go to a place which smells in a specific way,

The way blind experience space is not as if nothing is around, but for the blind, the sensorium is around the body itself. So for the blind things are there even when the things are not there for a person with eyesight. Everything becomes a sensory tunnel that images through various senses. Like when you go to a garden, the blind does not experience the garden he experiences the garden through a continuous series of the sensory tunnel by various senses. All of that creates that sensorium around. With eyesight, you get a sense that it is wide open but in that sense, the blind sees much more than a person with eyesight. The sensorium is the tunnel.

(Read More)

Senses are typically considered as separate entities that act individually yet all the senses work together in synchronization of each other to provide a cohesive experience of space. The contribution of each sense is equal in power, yet unique in character. In a space, emotive characters are induced by sensory cues. These can be visual, auditory, olfactory, environmental, or haptic cues of any nature.

Recalling some of my personal experiences such as visiting Golconde in Pondicherry was such that there was an experience in the transition of how the space transformed from a private room to a room that opened up to the corridor and then the corridor opened up to the outside. In the case of Lunuganga in Sri Lanka, when I entered a building designed by Geoffrey Bawa, it evoked a sense of pleasure that goes perfectly with the climate, culture, and landscape of Sri Lanka. A seamless transition between the landscape and the built unbuilt. Both of these experiences of transience and pleasure for me emerged on the reliance of using sight as a tool to experience these spaces.

However, I feel that these spaces get accessed and experienced differently by entities with an absence of a particular sense. The majority of our built environment is designed for people who can hear, walk, look with little regard for how the walking, talking, and hearing-impaired navigate and sense space through their different senses. For the differently-abled, the absence of one of the senses makes other senses sharper and more active, and thus the experience of space itself is a unique sensorium that I wish to interrogate in this thesis. I am exploring the possibilities of how a person without a sense of sight, senses, and experiences space through his other senses. Because of seeing, the sighted has developed a certain way of seeing, where the world is becoming more ocular centric.

To understand different senses, references that were referred to are Phenomenology of perception by Maurie Merleau Ponty, The Eyes of the Skin by Juhani Pallasmaa, and Touching the Rock- An Experience of Blindness” by John Hull helped as the main reference for this thesis. After getting some insights, for digging deeper into it, I had conversations with people with a loss of sense of sight. Through that, I got detailed insights on how space is sensed by them. The sense of smell is universally understood; however, the emotions it evokes and the memories it restores vary on an individual basis. The sense of touch often provokes a different texture which is then associated with an object. The sense of hearing provides the ability to perceive sounds and understand the surrounding. The presence and absence of these senses thus render certain densities in the experience of space.

Through their experience, I undertook the drawing of the sensory landscape. The neighborhood drawing swatches act as a base drawing for exploring the sense landscape within the space. So the base drawing is then overlapped with the sensorium drawings. The sensorium drawings then represent how a blind explores or navigates the space through his senses such as hear, smell, and touch. The drawing of the sensorium reveals the factors of the tactility of the surfaces, the movement of air, the presence of generators of smell, the idea of materiality, all of that shapes the understanding of the space. So space is not limited to walls or boundaries, space is about tactility, comfortness increases when we go to a place which smells in a specific way,

The way blind experience space is not as if nothing is around, but for the blind, the sensorium is around the body itself. So for the blind things are there even when the things are not there for a person with eyesight. Everything becomes a sensory tunnel that images through various senses. Like when you go to a garden, the blind does not experience the garden he experiences the garden through a continuous series of the sensory tunnel by various senses. All of that creates that sensorium around. With eyesight, you get a sense that it is wide open but in that sense, the blind sees much more than a person with eyesight. The sensorium is the tunnel.

(Read More)

> Sense Landscape of animals in an intense human habitation - Devarsh Sheth

Cities are not only made up of people but also of the urban wildlife and this urban wildlife exists irrespective of our want and need. In every neighbourhood you walk through you find them inhabiting the intense human habitation. The urban form of the city allows for these multiple inhabitations where the neighbourhood acts as a home for these stray animals.

The thesis aims at understanding the idea of spatiality for urban wildlife, specifically dogs in an intense human neighbourhood and their relationships with humans and if this form of conviviality shapes the spatiality of the urban wildlife (dogs). Additionally, it explores the sense landscape of a dog in the streets of the neighbourhood.

Inorder to do this the fieldwork involved careful observations of my neighbourhood, Lallubhai Park, Andheri West, where I tried to understand the human animal behaviour such as animal moments, their places of rest, space to procure food/water and sheltering along with the different types of interactions with humans and other animals. These are mapped through the lens of an animal creating a sense landscape of a dog. The drawing method that I have explored is that of constructing a sensorium through these smells, the overall smell of the neighbourhood, geometry of the smell, flowy nature of smell, identification of pockets of comfort and enjoyment, layer of conviviality which led to a sensorium landscape of an animal in an intense neighbourhood.

These strange inhabitations allow different kinds of relationships to occur between humans and animals at multiple levels like feeding animals on a daily basis, taking care of the injured ones, just observing them or petting them, running pass through them, getting scared and many other forms of conviviality. By doing this strangers become friends, friends become family, instead of having one agency the stray animals start having multiple agencies that look after them in various ways and the entire neighbourhood starts making spaces for everyone to coexist. Thus the question that my research dwells in is what is the spatiality of this animal and human coexistence in neighbourhoods and what are the forms of conviviality shared beyond compassion, objectification and friendship between them?

The conclusions of the thesis reveals that the current urban form is odourless whereas the spaces of comfort and enjoyment for the dogs is the life of this urban form which activates the sense of smell through which they navigate. Thus, I further ask how would an activation of a sense (smell) affect the spatiality of the urban form of this human neighbourhood?

(Read More)

> Pet Landscapes: Spatial awkwardities in human-animal interactions - Paulomi Joshi

Over time, as human-animal interactions have emerged, changed, and evolved, the animal has become an ingrained part of the city. From stray and domestic to house-pets, these animals engage with the urban fabric at various levels. Out of these, the pet has become an emotional commodity and companion or an object of pleasure, and hence a common occurrence. This has brought about shared spatialities within the built environment. The animal understands these shared spaces, on one hand, by their perceptions and on the other through the ever-present control exerted by the humans. This research tries to explore the pet-human bonds and a pet’s inhabitation of the shared spaces emerging from these bonds. It aims to understand the spatiality that is constructed for an animal, particularly dogs, in an intensely domestic human space.

The study is conducted parallelly in two parts, readings and secondary research, and field study. The readings explored are about animal psychology, physiology, sensibilities, etc, to build an analytical framework for the field study. Reading from the works of people like Alexandra Horowitz, Per Jensen, Konrad Lorenz, Jacob Von Uxkull, Franz Kafka, Natsumi Soseki, among others, identification of the parameters governing the animal in domestic spaces is achieved. These parameters bring forth the idea of the ‘Sensorium’, which becomes the basis for the field study. The method followed by the fieldwork is first - identification of the three cases, and then further building a structure to analyze these cases. Based on the parameters identified through the readings and the observations, the drawings work as analytical tools to map the occupation of the space by pet dogs, by plotting the sensescapes and certain parameters that input into them.

The difference in the perception of the dog and the human means that the space affords different opportunities and possibilities to each. Depending on this, and the underlying level of comfort and emotion, space either becomes a ‘place of rest, play, hiding, exploration, escape’ etc, with different characteristics for each. Depending on the need, space is constructed in different forms. Based on these findings, spaces can be rethought of through these parameters. The approach to design can change from visual and human-centric to a more multi-specie friendly, multi-sensory approach.

(Read More)

02 / Mediatized Environments

> “Switch”ed city: Architecture of mediatised sensory hardware extensions - Kalpita Salvi

The year 2020 has shifted methods of institutional operations. For years, people used to travel miles to attend a meeting, seminar or a lecture. Today, these tasks are performed just by sitting home in front of a screen. This has shifted older relations and dismantled clear categories of work, living, leisure as well as neat identity categories such as families, friends, colleagues etc. Over the years, devices with the suffix ‘ware’ have become an integral part of our everyday tasks. Keller Easterling discusses the idea of ‘ware’ as a modifier of intelligence, to suggest a transformation of contemporary culture. Today mediatised hardware devices are enhancing or diminishing our senses to connect to different spatial cartographies, creating various sensoriums around an individual. It makes the human body project itself and interact with hardware, data and space in this new medium of the digital sensorium. Reading from the research and theories by Marshall McLuhan and Michel Foucault, this thesis focuses on the spatialities created by the media extension hardwares and how it affects human societies by expanding their sensoriums. Here, the media and medium are taken as important elements of generators of space. The theoretical framework set up in the dissertation is used to map these spatial changes and the new experiences of space.

The field of study is a suburb of Mumbai called Goregaon. The stories are based in five geographies of the city, in a typical Goregaon apartment, a gated community, on a typical street, on a local transport and in a community event. The thesis works with semi fictional narratives written in the form of scripts and a graphic storyboard that allows for a spatio-temporal retelling of the experience.

The thesis identifies five frameworks of reading this space viz; heterotopias of the frame, city as a panopticon, a space calculator, the hallucinating neighbour and the digital smell. These spatio- temporal narrations allow a completely different reading of the geographies of the Goregaon suburban landscapes that speak of the complex mixing of categories and the new identifications of space produced through the mediatiated interfaces and their extended, often fragmented sensoriums.

(Read More)

The field of study is a suburb of Mumbai called Goregaon. The stories are based in five geographies of the city, in a typical Goregaon apartment, a gated community, on a typical street, on a local transport and in a community event. The thesis works with semi fictional narratives written in the form of scripts and a graphic storyboard that allows for a spatio-temporal retelling of the experience.

The thesis identifies five frameworks of reading this space viz; heterotopias of the frame, city as a panopticon, a space calculator, the hallucinating neighbour and the digital smell. These spatio- temporal narrations allow a completely different reading of the geographies of the Goregaon suburban landscapes that speak of the complex mixing of categories and the new identifications of space produced through the mediatiated interfaces and their extended, often fragmented sensoriums.

(Read More)

> Devicing Home - Aditya Verma

Present-day homes can not be imagined without the technologies they are embedded with. Adapting to and appropriating these technologies brings about a change in the occupancy and the social interactions within the lived space of the home. This research aims to understand how emerging technology has been incorporated and assimilated within the spatiality of the home. Further, it also aims to consider the revised and evolving semantics of our everyday domestic environment seen through the intervention of new technologies.

Technological devices become intrinsic to the planning and formulation of an apartment. Physical re-morphing and organization of spaces are ordinarily done in accordance with the everyday devices. My aim in this research is to examine the architectural impact of these technological transformations and provide a critical analysis of how these transformations affect the physical space of a house, structuring of spaces, and hence inhabitation. I will look at apartment houses (BHK Model) of Mumbai over the last 90 years and trace their evolution through three rooms; the bedroom, the living room (hall), and the kitchen by analyzing the domesticities, both imagined and emerging within these houses. Apartment becomes an imagination deeply intertwined in the consumption of a very distinct kind of life that happens around technological devices. They are targeted at the lifestyles which happen around appliances and for the residents presumably sharing the same disposition towards daily life as conventionally implied.

However, the traditional meanings and functions associated with the divisions of the apartment no longer reflect the activities that they hold. Houses have started to lend themselves to all different kinds of possibilities which are being enabled and facilitated by new technologies and with them emerging new kinds of practices and social relationships within the domestic space. Through this study, the thesis aims to open up a discussion on how apartment architecture can be readdressed through a renewed understanding of the techno-social evolutions over the last century.

(Read More)

Technological devices become intrinsic to the planning and formulation of an apartment. Physical re-morphing and organization of spaces are ordinarily done in accordance with the everyday devices. My aim in this research is to examine the architectural impact of these technological transformations and provide a critical analysis of how these transformations affect the physical space of a house, structuring of spaces, and hence inhabitation. I will look at apartment houses (BHK Model) of Mumbai over the last 90 years and trace their evolution through three rooms; the bedroom, the living room (hall), and the kitchen by analyzing the domesticities, both imagined and emerging within these houses. Apartment becomes an imagination deeply intertwined in the consumption of a very distinct kind of life that happens around technological devices. They are targeted at the lifestyles which happen around appliances and for the residents presumably sharing the same disposition towards daily life as conventionally implied.

However, the traditional meanings and functions associated with the divisions of the apartment no longer reflect the activities that they hold. Houses have started to lend themselves to all different kinds of possibilities which are being enabled and facilitated by new technologies and with them emerging new kinds of practices and social relationships within the domestic space. Through this study, the thesis aims to open up a discussion on how apartment architecture can be readdressed through a renewed understanding of the techno-social evolutions over the last century.

(Read More)

> Spatiality of publicness and new media - Tanvi Savla

A personal experience of instances like not allowing the access to a free-entry public place due to the appearance of a person, some places like streets which are too claimed and declared as no-hawking zones and sometimes personally being so engrossed in social media while outside, that there has been a complete re-purpose of the use of public spaces, made me think about it.

In our everyday life, “Public” plays an important role. From the road we walk on to parks we visit, everything comes under the idea of public space. We see various public places emerging over the period of time such as malls, parks, shopping centres, food hubs etc. for people to use and occupy in multiple forms. These spaces are usually built with the perspective of becoming a means of leisure. People are allowed to use these without any monetary investments, or sometimes with a very low maintenance fee. But these new public places are very restrictive to the type of users. Only specific forms of people become active users of these spaces.

Thus, the idea of public produces both, the interventions of anti-public and formation of a new public and that is where ‘Architecture’ becomes instrumental. In the current times, the advent of new media in our daily lives has changed our perspectives of looking at and perceiving the physicality of these varied forms of public spaces. There is a hijack or a loss of experience of these public spaces due to the dematerialization that has occurred on account of excess usage of internet driven media. Thus the thesis intends to understand these changes in experiences and routines with the coming up of new media and its subsequent dematerialization. What happens to life (routines, physical experiences, transactions, community formation, relationships, etc.) when spatiality of public space transforms on account of new media?

Thesis aims to look at following concepts of

The method that I employ to draw is that of collage / montage of spatial/temporal collapse using associated images with short annotations. Terms such as peripheral vision and involuntary senses become the driving force in the making of the drawing. New media with its benefits brings in a heightened experience of anxiety that makes our senses disoriented as the surroundings are blurred. Thus, a clear understanding may not be developed and hence generating a stimulus in our minds.

To conclude, new media has made the experience of public space simultaneous. We are in a physical space, but we also inhabit a virtual space simultaneously. The simultaneity that we experience dematerializes the experience of a particular space. The closed boundaries of a public space have thus become an infinite canvas to be explored. Neither the public space nor its edges are fixed. There is a constant reproduction of the experiences when one person enjoys a place physically and shares it to others through various internet driven devices. When multiple people can virtually be there at the same time, the need and form of physical space diminishes.

(Read More)

In our everyday life, “Public” plays an important role. From the road we walk on to parks we visit, everything comes under the idea of public space. We see various public places emerging over the period of time such as malls, parks, shopping centres, food hubs etc. for people to use and occupy in multiple forms. These spaces are usually built with the perspective of becoming a means of leisure. People are allowed to use these without any monetary investments, or sometimes with a very low maintenance fee. But these new public places are very restrictive to the type of users. Only specific forms of people become active users of these spaces.

Thus, the idea of public produces both, the interventions of anti-public and formation of a new public and that is where ‘Architecture’ becomes instrumental. In the current times, the advent of new media in our daily lives has changed our perspectives of looking at and perceiving the physicality of these varied forms of public spaces. There is a hijack or a loss of experience of these public spaces due to the dematerialization that has occurred on account of excess usage of internet driven media. Thus the thesis intends to understand these changes in experiences and routines with the coming up of new media and its subsequent dematerialization. What happens to life (routines, physical experiences, transactions, community formation, relationships, etc.) when spatiality of public space transforms on account of new media?

Thesis aims to look at following concepts of

- Public and public spaces

- New Media

- Publicness of media

The method that I employ to draw is that of collage / montage of spatial/temporal collapse using associated images with short annotations. Terms such as peripheral vision and involuntary senses become the driving force in the making of the drawing. New media with its benefits brings in a heightened experience of anxiety that makes our senses disoriented as the surroundings are blurred. Thus, a clear understanding may not be developed and hence generating a stimulus in our minds.

To conclude, new media has made the experience of public space simultaneous. We are in a physical space, but we also inhabit a virtual space simultaneously. The simultaneity that we experience dematerializes the experience of a particular space. The closed boundaries of a public space have thus become an infinite canvas to be explored. Neither the public space nor its edges are fixed. There is a constant reproduction of the experiences when one person enjoys a place physically and shares it to others through various internet driven devices. When multiple people can virtually be there at the same time, the need and form of physical space diminishes.

(Read More)

03 / Of Mobility and Publics

> The Politics of Commons - Ashi Chordia

I enjoy a sense of freedom in open shared places, beyond the confines of the house. These places are resources, shared by a collective, and inhabited through the practices of the everyday. It is the blurry ownerships that produces the experience of openness.

The term “commons'' refers to open resources that are shared among the public. Cultural theorists such as Elinor Ostrom speak of the idea of the commons as a resource, challenging views like those of Hardin’s that through the articulation of the ‘tragedy of the commons’ speaks of the impossibility of sharing resources. However these articulations are in the context of rural contexts. Very few theorists speak of the idea of urban commons and even when they do so, speak through simplistic relationships. My experience of commons on the other hand reveals them as deeply contested spaces. Therefore the question that emerges is: “How do the commons lend themselves to be appropriated by individuals who come together to practice their everyday?”

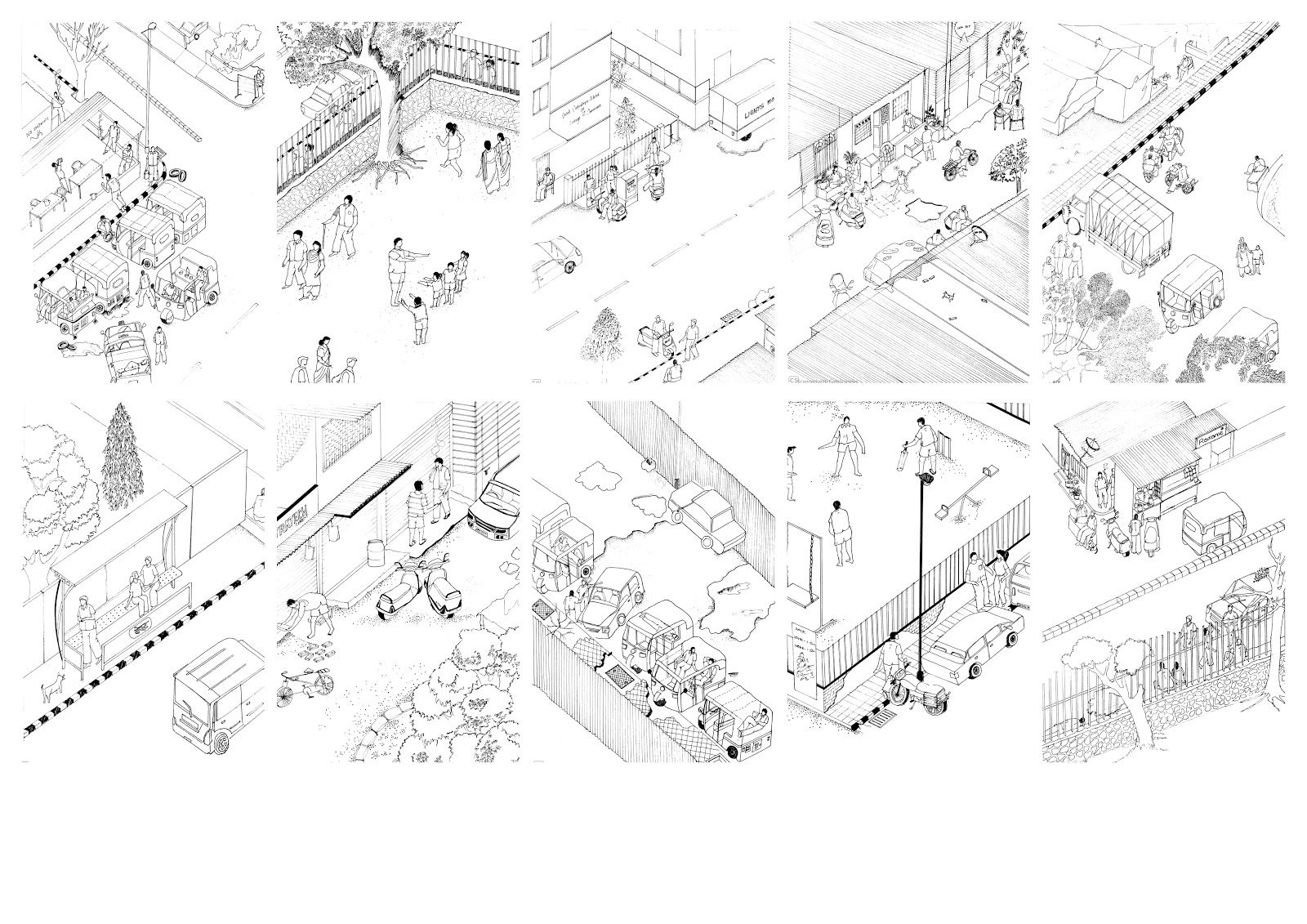

This thesis argues that communities are produced by the associations that are constructed through the practice of using and maintaining commons. The articulation of communities constructs the ‘other’ and therefore produces a politics within the communities itself to contest its inhabitation. It is not through resolutions but through this politics that the experience of commons (i.e. space) is produced. A close scrutiny uncovers the nuances of the politics of commons by analysing five different streets of Malad, Mumbai. The spatiality of these streets is realised through the stories of these shared spaces over the last three decades. These stories bring out negotiations between individuals from different backgrounds and collective communities, which came together to live with each other.

Hence, this study builds towards an approach of decreasing restrictions in the outdoor areas by producing imaginations of spaces which affords negotiations, spaces which allow many more multiciplities to happen, finding ways to soften the existing power structures and hierarchies that they set up in accessing the commons, in favour of a more egalitarian space.

(Read More)

The term “commons'' refers to open resources that are shared among the public. Cultural theorists such as Elinor Ostrom speak of the idea of the commons as a resource, challenging views like those of Hardin’s that through the articulation of the ‘tragedy of the commons’ speaks of the impossibility of sharing resources. However these articulations are in the context of rural contexts. Very few theorists speak of the idea of urban commons and even when they do so, speak through simplistic relationships. My experience of commons on the other hand reveals them as deeply contested spaces. Therefore the question that emerges is: “How do the commons lend themselves to be appropriated by individuals who come together to practice their everyday?”

This thesis argues that communities are produced by the associations that are constructed through the practice of using and maintaining commons. The articulation of communities constructs the ‘other’ and therefore produces a politics within the communities itself to contest its inhabitation. It is not through resolutions but through this politics that the experience of commons (i.e. space) is produced. A close scrutiny uncovers the nuances of the politics of commons by analysing five different streets of Malad, Mumbai. The spatiality of these streets is realised through the stories of these shared spaces over the last three decades. These stories bring out negotiations between individuals from different backgrounds and collective communities, which came together to live with each other.

Hence, this study builds towards an approach of decreasing restrictions in the outdoor areas by producing imaginations of spaces which affords negotiations, spaces which allow many more multiciplities to happen, finding ways to soften the existing power structures and hierarchies that they set up in accessing the commons, in favour of a more egalitarian space.

(Read More)

> The spatiality of urban mobilities: Shaping our experience of everyday - Abhinav Pahade

The city is a phenomenon, produced in movement. City forms can be viewed as sediments of actions and movements, and the consolidation of these allows for the production of varied spatialities. A different construct of the city exists in people's minds, based on the mobilities they perceive the city through - which can be understood as their spatiality of mobility. Leaning on phenomenological ideology, we understand that an individual’s identity always affects how they perceive the world around them - therefore, attention is consciously drawn to the role of the individual and their identity, throughout this study. Using a framework to understand the interdependencies of the city, its spaces and the multiple mobilities it contains, we can establish a fundamental link between the role of perception and an individual’s lived experiences.

This paper explores the question, “How do contemporary mobilities shape our spatiality and experience of the urban everyday?". The study uses data collected from social experiments, interviews and extended interactions conducted with a set sample of Mumbai city dwellers chosen from across spectrums of age, gender and socioeconomic classes - allowing for inferences and comparisons between spatialities based on identity. The research method was designed to help reveal how the same urban space can instigate varied experiences for the same individual, depending upon the rate at which they conduct their mobility.

The research uncovers how varying speeds alter the extent to which our identities play a role in shaping our experiences. The data collected, hints at the impact of speed on our sensory capabilities and registry which arguably results in spatialities across identities, homogenising at higher rates of mobility. The study positively reveals the role of speed in shaping our spatiality.

(Read More)

This paper explores the question, “How do contemporary mobilities shape our spatiality and experience of the urban everyday?". The study uses data collected from social experiments, interviews and extended interactions conducted with a set sample of Mumbai city dwellers chosen from across spectrums of age, gender and socioeconomic classes - allowing for inferences and comparisons between spatialities based on identity. The research method was designed to help reveal how the same urban space can instigate varied experiences for the same individual, depending upon the rate at which they conduct their mobility.

The research uncovers how varying speeds alter the extent to which our identities play a role in shaping our experiences. The data collected, hints at the impact of speed on our sensory capabilities and registry which arguably results in spatialities across identities, homogenising at higher rates of mobility. The study positively reveals the role of speed in shaping our spatiality.

(Read More)

> Highway urbanization: The architecture of flux, uncertainty and anticipation - Ankita Teli

How does a highway reshape the spatiality of a village settlement? This question is framed in the backdrop of an emerging urbanization shaped by the expansion of existing or construction of new highways along India’s inter-city corridors, which intend to reduce travel time for the movement of goods and people, and boost tourism. There are three ways in which existing literature in the urban studies and architecture field discusses such transformations: first, through the dispossession that the land acquisition for such projects lead to and the challenge for collective action; second, the potential of new land based collectives to establish shareholder cities; and third, the possibilities of manifesting vernacular and regional identities in the ongoing architecture through tectonic explorations in architectural design. At stake in my question lies the challenge to open up ways of thinking about transforming spatialities that raise new architectural questions beyond the above discussions.

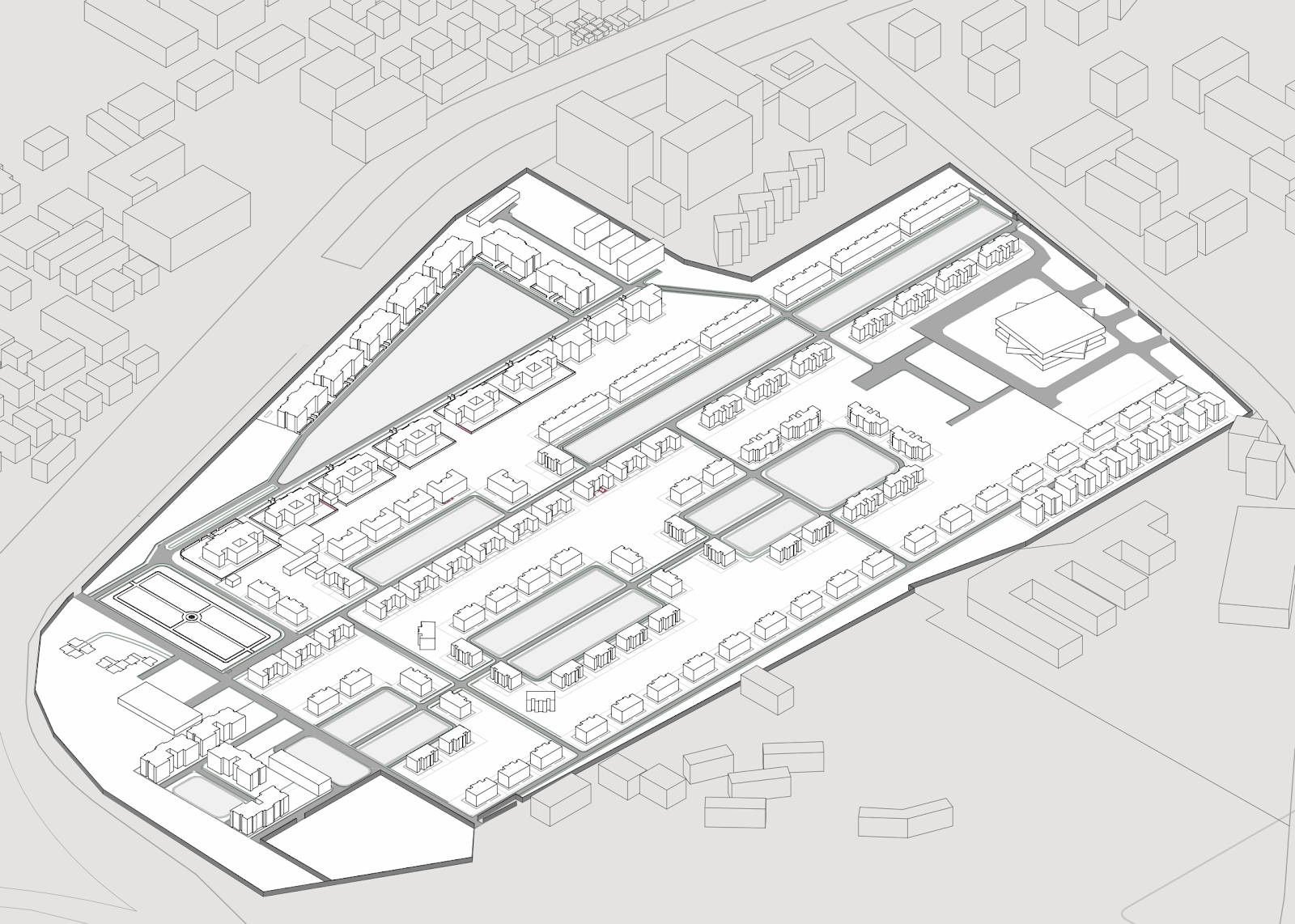

I explore my research question in Talere village (2,211 population, 2011 Census) located in Kankavli Tehsil of Sindhudurg district along Mumbai-Goa National Highway (NH66), which runs north-south along India’s west coast. Highway expansion here has led to significant socioeconomic and spatial changes, which is also my native place. Given the context of COVID-19 quarantine, I managed to mobilize my kinship networks in the village to locate fifteen households who owned property along the highway and became my field interlocutors. I conducted audio and video interviews with the heads of these households (ten with builtform + five with agricultural land) along the highway to understand the household configurations, livelihoods and spatiality of each property before and after the highway expansion. I drew on Google Earth as well as archival photographs gathered from these households to make architectural drawings. The narrative of the ongoing change is structured as a story of the spatiality before and after highway expansion in a way that combines plans, sections, axonometrics along with rich quantitative and qualitative data that I tapped from the interviews, which has helped me shape three arguments.

First, I argue that the flux of Talere’s urban transition, which has been intensified by the highway expansion, has led to the demand for new programmatic and spatial types of builtform because its highway node is emerging as a night stopover for travelling tourists, and for short and medium term migrants like micro-entrepreneurs selling goods in the weekly market, students, government school teachers and construction workers. This has led to the generation of new programmatic types of builtform in the village such as hotels, shopping centres and rental housing. A single spatial type has emerged in response to these new programmes: single-loaded corridor attached to multiple cells (units) for living or commerce.

Second, the uncertainty of the economic flux has led to each household’s practice of anticipating the future of their property. Household members speculate their futures and for their properties by calculating their individual capacities within the context of the new possibilities opened up by Talere as a highway node, plot location and adjacencies, and ways in which to stake property shares in the joint family household. Although not completely sure of the profits that the anticipated future might bring, households nevertheless invest into building. The emergence of a new single spatial type needs - single-loaded corridor attached to multiple cells - for a diversity of new programmes needs to be understood in the context of such uncertainty and anticipation in the economic flux.

And third, I argue that in the articulation of the new builtform, there has emerged a schism between the exigencies of the fast movement corridor, on the one hand, and the cultural form of existing living practices, on the other hand. This schism manifests in the grafting of the new spatial types into properties that earlier consisted of smaller shop houses, the edges of the new builtform along the highway which neither responds to the fast moving vehicles nor to their use as commons, and even to the construction of new buildings that might drastically reduce or create new opportunities for adjacent properties. This scenario poses new questions for architects who have largely focused on the village as a source of vernacular and regional identities: How can architects design spatialities and buildings that are nimble to adapt to the practices of anticipation in an uncertain economy? What is the architecture of flux and uncertainty?

(Read More)

I explore my research question in Talere village (2,211 population, 2011 Census) located in Kankavli Tehsil of Sindhudurg district along Mumbai-Goa National Highway (NH66), which runs north-south along India’s west coast. Highway expansion here has led to significant socioeconomic and spatial changes, which is also my native place. Given the context of COVID-19 quarantine, I managed to mobilize my kinship networks in the village to locate fifteen households who owned property along the highway and became my field interlocutors. I conducted audio and video interviews with the heads of these households (ten with builtform + five with agricultural land) along the highway to understand the household configurations, livelihoods and spatiality of each property before and after the highway expansion. I drew on Google Earth as well as archival photographs gathered from these households to make architectural drawings. The narrative of the ongoing change is structured as a story of the spatiality before and after highway expansion in a way that combines plans, sections, axonometrics along with rich quantitative and qualitative data that I tapped from the interviews, which has helped me shape three arguments.

First, I argue that the flux of Talere’s urban transition, which has been intensified by the highway expansion, has led to the demand for new programmatic and spatial types of builtform because its highway node is emerging as a night stopover for travelling tourists, and for short and medium term migrants like micro-entrepreneurs selling goods in the weekly market, students, government school teachers and construction workers. This has led to the generation of new programmatic types of builtform in the village such as hotels, shopping centres and rental housing. A single spatial type has emerged in response to these new programmes: single-loaded corridor attached to multiple cells (units) for living or commerce.

Second, the uncertainty of the economic flux has led to each household’s practice of anticipating the future of their property. Household members speculate their futures and for their properties by calculating their individual capacities within the context of the new possibilities opened up by Talere as a highway node, plot location and adjacencies, and ways in which to stake property shares in the joint family household. Although not completely sure of the profits that the anticipated future might bring, households nevertheless invest into building. The emergence of a new single spatial type needs - single-loaded corridor attached to multiple cells - for a diversity of new programmes needs to be understood in the context of such uncertainty and anticipation in the economic flux.

And third, I argue that in the articulation of the new builtform, there has emerged a schism between the exigencies of the fast movement corridor, on the one hand, and the cultural form of existing living practices, on the other hand. This schism manifests in the grafting of the new spatial types into properties that earlier consisted of smaller shop houses, the edges of the new builtform along the highway which neither responds to the fast moving vehicles nor to their use as commons, and even to the construction of new buildings that might drastically reduce or create new opportunities for adjacent properties. This scenario poses new questions for architects who have largely focused on the village as a source of vernacular and regional identities: How can architects design spatialities and buildings that are nimble to adapt to the practices of anticipation in an uncertain economy? What is the architecture of flux and uncertainty?

(Read More)

04 / Many appearances of streets

> Street as a Carnival - Simran Panchal

In a city/locality which is planned and follows a strong grid, there are activities that are not thought of while planning it. Some of these activities are considered as “inappropriate” by society and there are people who are considered as deviant bodies who are not allowed to enter within a space because they do not fall under the normative idea of beauty and other norms that are created by the society. This leads to the question: what is a neutral space which can allow all kinds of bodies to inhabit it?

The thesis aims to understand the spatiality of neutral spaces that can allow everyone in, without creating any differences, where deviant bodies, people who do not fall under the normative categories of beauty in society are allowed without anyone judging them. A space where one can enact their activities and practice and produce their own space. It also aims to understand the affordance of space that allows everyone to enact these activities and practice and produce their own space.

The thesis argues that a carnival is such a space that allows multiple bodies to simultaneously inhabit space. The philosopher Bakhtin speaks of the carnival as a space that breaks the idea of hierarchies and allows everyone to escape from the reality without any/few restrictions. The image of the Carnivalesque talks about the playful spirit of the carnival in which there is no idea of authority. It focuses on laughter, role reversal, dressing up, and a place where multiple conversations take place simultaneously. Here normative ideas of the dirty and unclean do not exist.

The carnival allows and opens up a new world for a lot of people who cannot enact and be themselves in the real world. Bhaktin also describes carnivals as ‘second life’ for people.

The thesis looks at a stretch of a street in Charkop, Mumbai as its field. Though this is a part of the city that follows a restrictive gridded development, life spills out of the grid-like a carnival. When seen through the metaphor of the carnival as the most neutral space, the street opens up many possibilities for simultaneous practices and productions of space. It allows people to create conviviality amongst each other and enact their activities and practices while producing their own space. It thus tries to establish a relationship between the carnival-like nature of the street in Charkop which tends to behave like a neutral space in the city.

To conclude the dissertation tries to look at a carnival-like support infrastructure that can blur the boundaries between the planned nature of the city/locality and the activities that take place in it that are not planned for, which ultimately lends itself to becoming a neutral space in the city.

(Read More)

The thesis aims to understand the spatiality of neutral spaces that can allow everyone in, without creating any differences, where deviant bodies, people who do not fall under the normative categories of beauty in society are allowed without anyone judging them. A space where one can enact their activities and practice and produce their own space. It also aims to understand the affordance of space that allows everyone to enact these activities and practice and produce their own space.

The thesis argues that a carnival is such a space that allows multiple bodies to simultaneously inhabit space. The philosopher Bakhtin speaks of the carnival as a space that breaks the idea of hierarchies and allows everyone to escape from the reality without any/few restrictions. The image of the Carnivalesque talks about the playful spirit of the carnival in which there is no idea of authority. It focuses on laughter, role reversal, dressing up, and a place where multiple conversations take place simultaneously. Here normative ideas of the dirty and unclean do not exist.

The carnival allows and opens up a new world for a lot of people who cannot enact and be themselves in the real world. Bhaktin also describes carnivals as ‘second life’ for people.

The thesis looks at a stretch of a street in Charkop, Mumbai as its field. Though this is a part of the city that follows a restrictive gridded development, life spills out of the grid-like a carnival. When seen through the metaphor of the carnival as the most neutral space, the street opens up many possibilities for simultaneous practices and productions of space. It allows people to create conviviality amongst each other and enact their activities and practices while producing their own space. It thus tries to establish a relationship between the carnival-like nature of the street in Charkop which tends to behave like a neutral space in the city.

To conclude the dissertation tries to look at a carnival-like support infrastructure that can blur the boundaries between the planned nature of the city/locality and the activities that take place in it that are not planned for, which ultimately lends itself to becoming a neutral space in the city.

(Read More)

> (Inter-)active Spaces - Saloni Vora

“If space does not have boundaries, do things then extend infinitely?”- Tschumi Bernard. 1989, Question of Space. New York: Architectural Association Publications.

Cities are formed by various forms of boundaries. Boundary is the ‘in between space’ which should be understood as a space for growing interactions and blurring the boundaries of inside and outside. In between spaces are spread across the city in fragments. They are perceived as dead zones which are under utilised and imagined as filthy, whereas the rigidness of distinct boundaries serve one dimensional use for division of plots but are often apprehended as clean and clear edges. These edges allow transactions to take place and make the space flexible. The continuous fluctuating realm of growing and shrinking, shapes the relationship between the user and the built environment.

The interactions between the form and the function of the space started vanishing as development took over. On comparing the past geographies of my neighbourhood, Malad, a suburb in Mumbai, there is no interaction between the form and the function with the space which used to be in 1980s. Borrowing and building on works of J. Gibson’s theory of furnished environment and affordance of space, Benjamin N. Vis’ book which talks about creating transparency in humans and social interactions and Lukas Smas explaining transactional spaces as the in-between spaces which creates a blur in the inside and the outside. Thus I further want to expand my thesis on the concepts of transactional capacity and affordance of space through strategies which reveals the subjective sense of space.

The interaction with physical boundaries differs from imaginary boundaries which creates a difference in the type of activities performed. To achieve the hypothesis three different edge conditions would be studied through the method of mapping and infographics. This will help to understand time-geography of the place and put together a study in time and space. Thus a comparison will be created on comparing the transactional capacity of the space and reveal its affordance of form. Through this I have identified that there are specific conditions of not only cultural production and desire but also stationary activities that people voluntarily or involuntarily utilize in their daily routine, which produces pockets of spaces all across the city.

This work is concerned with understanding the relationship of the form of the boundary and urban everyday life in the cities being formed, reformed and interdependent on each other. Within this broad theme the specific focus is on how humans inhabit in the built environment and the social life it creates. Considering the process, observation and inference it is distinct to conclude in two ways, that a human body experience adaptations and adjustments so frequently to the extent that consciously the user isn't aware of its extent and impact and also how the configuration of the form affects the affordance and the transactional capacity of the edge. As architects it's our role to understand what is the form of architecture which allows porosity?

(Read More)

Cities are formed by various forms of boundaries. Boundary is the ‘in between space’ which should be understood as a space for growing interactions and blurring the boundaries of inside and outside. In between spaces are spread across the city in fragments. They are perceived as dead zones which are under utilised and imagined as filthy, whereas the rigidness of distinct boundaries serve one dimensional use for division of plots but are often apprehended as clean and clear edges. These edges allow transactions to take place and make the space flexible. The continuous fluctuating realm of growing and shrinking, shapes the relationship between the user and the built environment.

The interactions between the form and the function of the space started vanishing as development took over. On comparing the past geographies of my neighbourhood, Malad, a suburb in Mumbai, there is no interaction between the form and the function with the space which used to be in 1980s. Borrowing and building on works of J. Gibson’s theory of furnished environment and affordance of space, Benjamin N. Vis’ book which talks about creating transparency in humans and social interactions and Lukas Smas explaining transactional spaces as the in-between spaces which creates a blur in the inside and the outside. Thus I further want to expand my thesis on the concepts of transactional capacity and affordance of space through strategies which reveals the subjective sense of space.

The interaction with physical boundaries differs from imaginary boundaries which creates a difference in the type of activities performed. To achieve the hypothesis three different edge conditions would be studied through the method of mapping and infographics. This will help to understand time-geography of the place and put together a study in time and space. Thus a comparison will be created on comparing the transactional capacity of the space and reveal its affordance of form. Through this I have identified that there are specific conditions of not only cultural production and desire but also stationary activities that people voluntarily or involuntarily utilize in their daily routine, which produces pockets of spaces all across the city.

This work is concerned with understanding the relationship of the form of the boundary and urban everyday life in the cities being formed, reformed and interdependent on each other. Within this broad theme the specific focus is on how humans inhabit in the built environment and the social life it creates. Considering the process, observation and inference it is distinct to conclude in two ways, that a human body experience adaptations and adjustments so frequently to the extent that consciously the user isn't aware of its extent and impact and also how the configuration of the form affects the affordance and the transactional capacity of the edge. As architects it's our role to understand what is the form of architecture which allows porosity?

(Read More)

> Reading the city: fragmenting the narrative - Maitreyee Rele

If I were to ask you what are the last five things you noticed in the city, what would your answer be? What is the image of the city that forms in your head? This thesis is an exploration of how cities are registered.

Cities are drawn, planned and understood through master plans and as a group of homogeneous clusters of spaces. They are given one single narrative, but often that is not how people experience and remember the space. In this dissertation, I study the different relationships that people have with the city and how these relations change the way they register the city. Through previous studies of people like Kevin Lynch, Aldo Rossi, Walter Benjamin, Virginia Woolf and Michel De Certeau I understand that spaces are a product of their physicality, their psycho-spatial aspects and how they are practiced. This makes them heterogeneous bulbous masses filled with textures, images, experience, stories and associations.

In order to understand if there are any patterns in these psycho spatial experiences of cities, I studied 10 sets of people from diverse classes, genders and age groups. I recorded their descriptions of their walks and what they registered of the city in the process. I found that there are four distinct ways in which people tend to register spaces in a city, these are – through lists, as sensoriums, as a series of events and as stories, real and imaginary. I realised that these multiple readings of a city open up multiple imaginations of the ways in which cities are inhabited by a host of people. These textures are often missed in simplistic cartographic readings of cities. The potential that this research offers is a way to build and intervene thoughtfully in a city that will take into account micro narratives, unique histories and specificities.

(Read More)

Cities are drawn, planned and understood through master plans and as a group of homogeneous clusters of spaces. They are given one single narrative, but often that is not how people experience and remember the space. In this dissertation, I study the different relationships that people have with the city and how these relations change the way they register the city. Through previous studies of people like Kevin Lynch, Aldo Rossi, Walter Benjamin, Virginia Woolf and Michel De Certeau I understand that spaces are a product of their physicality, their psycho-spatial aspects and how they are practiced. This makes them heterogeneous bulbous masses filled with textures, images, experience, stories and associations.

In order to understand if there are any patterns in these psycho spatial experiences of cities, I studied 10 sets of people from diverse classes, genders and age groups. I recorded their descriptions of their walks and what they registered of the city in the process. I found that there are four distinct ways in which people tend to register spaces in a city, these are – through lists, as sensoriums, as a series of events and as stories, real and imaginary. I realised that these multiple readings of a city open up multiple imaginations of the ways in which cities are inhabited by a host of people. These textures are often missed in simplistic cartographic readings of cities. The potential that this research offers is a way to build and intervene thoughtfully in a city that will take into account micro narratives, unique histories and specificities.

(Read More)

05 / On Beauty and Culture

> Interrogating Beauty: In houses of Amravati - Saloni Soni

I held certain ideas about beauty in mind, which have been developed through my four years of architectural education, however, on ground, it manifests very differently. When I observe my own neighborhood with a certain notion of beauty back in my head, what I see is completely different. Beauty as articulated by the client on the field in the process of realizing a home, is different from that through which architecture is conceived in the classroom. What are these gaps and how do they become different?

This thesis pursues the above question within the spatial practice of surroundings which I see everyday. How do aesthetic sensibilities get mobilized within everyday spatial practice by the aspirations and ambitions of a particular class of people while building their own houses. A close study of these everyday environments allow me to open up the concepts of beauty, aesthetic and space.

The fieldwork includes the interviews of seven varied houses in my neighborhood. It aims to understand different stories of these houses, how it was built, what were the requirements, how certain aesthetic and functional decisions were made? The conclusion tries to note the forces through which people settle for the expression of their own houses. It also looks at the similarities and their idea of beauty. The study helps to accept and empathize different ideas of beauty that are held in the field. It is an exploratory thesis which expands my own biases which I held in space.

(Read More)

This thesis pursues the above question within the spatial practice of surroundings which I see everyday. How do aesthetic sensibilities get mobilized within everyday spatial practice by the aspirations and ambitions of a particular class of people while building their own houses. A close study of these everyday environments allow me to open up the concepts of beauty, aesthetic and space.

The fieldwork includes the interviews of seven varied houses in my neighborhood. It aims to understand different stories of these houses, how it was built, what were the requirements, how certain aesthetic and functional decisions were made? The conclusion tries to note the forces through which people settle for the expression of their own houses. It also looks at the similarities and their idea of beauty. The study helps to accept and empathize different ideas of beauty that are held in the field. It is an exploratory thesis which expands my own biases which I held in space.

(Read More)

> Space of Inhabitation & its relationship with the Artistic experience - Manish Shravane

The thesis starts with the question how does spatiality of inhabitation shape artistic thinking? For this, one has to define both inhabitation and artistic thinking.

For defining artistic thinking I refer to several philosophers like John Dewey and Gaston Bachelard. According to these philosophers, whatever we see and do in our day to day life is an aesthetic experience. It is the ‘experience’ that we sometimes ignore, don't grasp or blur out and move on. For better understanding of ‘experience’, I refer to the physicist Richard Feynman's "Ode to the Flower". He tells the story of his disagreement with an artist who argued about who can better appreciate the beauty of a flower: artists or scientists. To hear Feynman tell it, the artist believed that a deep scientific understanding actually removed some appreciation of the flower as simply a beautiful thing. In other words, knowing the processes that created a thing could detract from appreciation of that thing. Whereas Feyman said, “I can appreciate the beauty of a flower. At the same time, I see much more about the flower than he sees. I could imagine the cells in there, the complicated actions inside, which also have a beauty. I mean it’s not just beauty at this dimension, at one centimeter; there’s also beauty at smaller dimensions, the inner structure, also the processes. The fact that the colors in the flower evolved in order to attract insects to pollinate it is interesting; it means that insects can see the color. It adds a question: does this aesthetic sense also exist in the lower forms? Why is it aesthetic?” These are questions that produce an intensity of life. An artist is one who goes through those experiences and produces art.

Art need not be a mystery. Art involves thinking. Thinking is never fixed. I think ‘artistic thinking’ means the way of looking at a problem or situation in fresh perspective also as an opportunity. For many artists, imaginative thought may arise during the process of making. In this social,cultural practices and beliefs also shape artistic ways of thinking. On studying philosophers like Baudelaire and Nietsche, I further argue that artistic experience comes through the intensity of living life.

‘Space of Inhabitation’, can also be defined in multiple ways. Inhabitation may be temporary space where we spend our valuable time, example, time spent at the work space, walking on street, sitting in public space ( play ground, movie theater, market, gymkhana,neighbours house etc.) In all of these situations we go through unique experiences. Depending on the nature of the space, we learn something, feel, think and then act accordingly. Therefore the question arises here, does the nature of inhabitation affect our imaginative thinking?

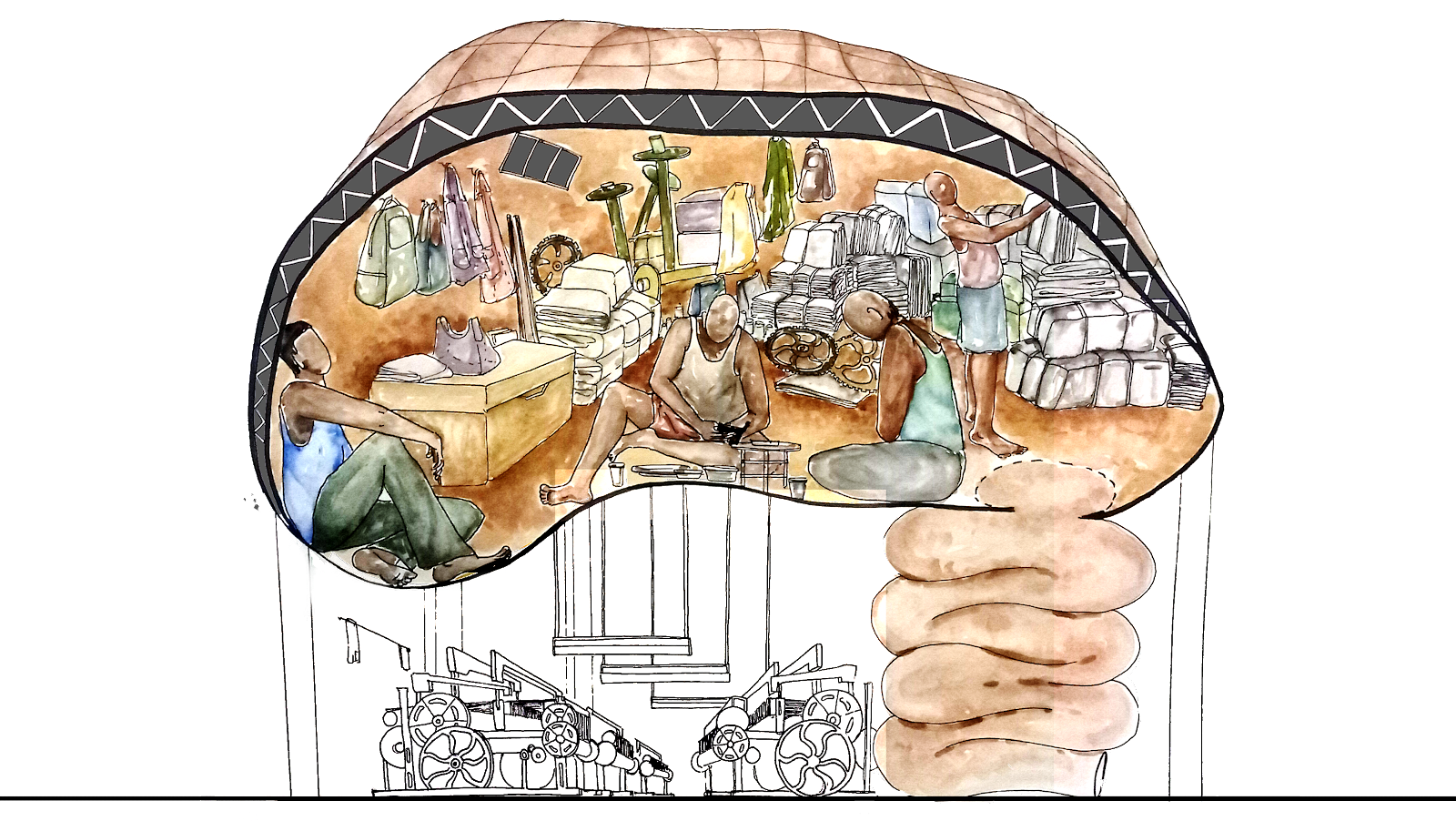

In order to understand this I studied four artistic practices and their inhabitations. Through the four cases I was able to extend the argument that artistic experience comes from the intensity of living. In the first case, an artistic experience is shaped through the multiplicity of the idea of home as neighbourhood at one scale and the idea of home as universe on the other, and through the multiplicity of stories that shape this inhabitation. The second case shows an artistic experience is produced through intense overlaps of spaces as the home and the karkhana intertwine to produce a density of experiences. In the third case, artistic experience is realised through intense dynamic atmospheres, where the gymkhana is kind of an extension to artistic practices that shapes the nature of space. The Fourth experience shows how intensity of experience is produced through engagements with labour that produces cities and the materiality of the art experience encompasses dust, and tattoos and powadas.

The structure of my drawings that record these artistic experiences also inhabit this intensity and density.

The corollary for architectural design processes, would then be what kind of inhabitation could generate dense artistic experiences?

(Read More)

For defining artistic thinking I refer to several philosophers like John Dewey and Gaston Bachelard. According to these philosophers, whatever we see and do in our day to day life is an aesthetic experience. It is the ‘experience’ that we sometimes ignore, don't grasp or blur out and move on. For better understanding of ‘experience’, I refer to the physicist Richard Feynman's "Ode to the Flower". He tells the story of his disagreement with an artist who argued about who can better appreciate the beauty of a flower: artists or scientists. To hear Feynman tell it, the artist believed that a deep scientific understanding actually removed some appreciation of the flower as simply a beautiful thing. In other words, knowing the processes that created a thing could detract from appreciation of that thing. Whereas Feyman said, “I can appreciate the beauty of a flower. At the same time, I see much more about the flower than he sees. I could imagine the cells in there, the complicated actions inside, which also have a beauty. I mean it’s not just beauty at this dimension, at one centimeter; there’s also beauty at smaller dimensions, the inner structure, also the processes. The fact that the colors in the flower evolved in order to attract insects to pollinate it is interesting; it means that insects can see the color. It adds a question: does this aesthetic sense also exist in the lower forms? Why is it aesthetic?” These are questions that produce an intensity of life. An artist is one who goes through those experiences and produces art.

Art need not be a mystery. Art involves thinking. Thinking is never fixed. I think ‘artistic thinking’ means the way of looking at a problem or situation in fresh perspective also as an opportunity. For many artists, imaginative thought may arise during the process of making. In this social,cultural practices and beliefs also shape artistic ways of thinking. On studying philosophers like Baudelaire and Nietsche, I further argue that artistic experience comes through the intensity of living life.

‘Space of Inhabitation’, can also be defined in multiple ways. Inhabitation may be temporary space where we spend our valuable time, example, time spent at the work space, walking on street, sitting in public space ( play ground, movie theater, market, gymkhana,neighbours house etc.) In all of these situations we go through unique experiences. Depending on the nature of the space, we learn something, feel, think and then act accordingly. Therefore the question arises here, does the nature of inhabitation affect our imaginative thinking?

In order to understand this I studied four artistic practices and their inhabitations. Through the four cases I was able to extend the argument that artistic experience comes from the intensity of living. In the first case, an artistic experience is shaped through the multiplicity of the idea of home as neighbourhood at one scale and the idea of home as universe on the other, and through the multiplicity of stories that shape this inhabitation. The second case shows an artistic experience is produced through intense overlaps of spaces as the home and the karkhana intertwine to produce a density of experiences. In the third case, artistic experience is realised through intense dynamic atmospheres, where the gymkhana is kind of an extension to artistic practices that shapes the nature of space. The Fourth experience shows how intensity of experience is produced through engagements with labour that produces cities and the materiality of the art experience encompasses dust, and tattoos and powadas.

The structure of my drawings that record these artistic experiences also inhabit this intensity and density.

The corollary for architectural design processes, would then be what kind of inhabitation could generate dense artistic experiences?

(Read More)

> Culture in my backyard - Harsh Vora

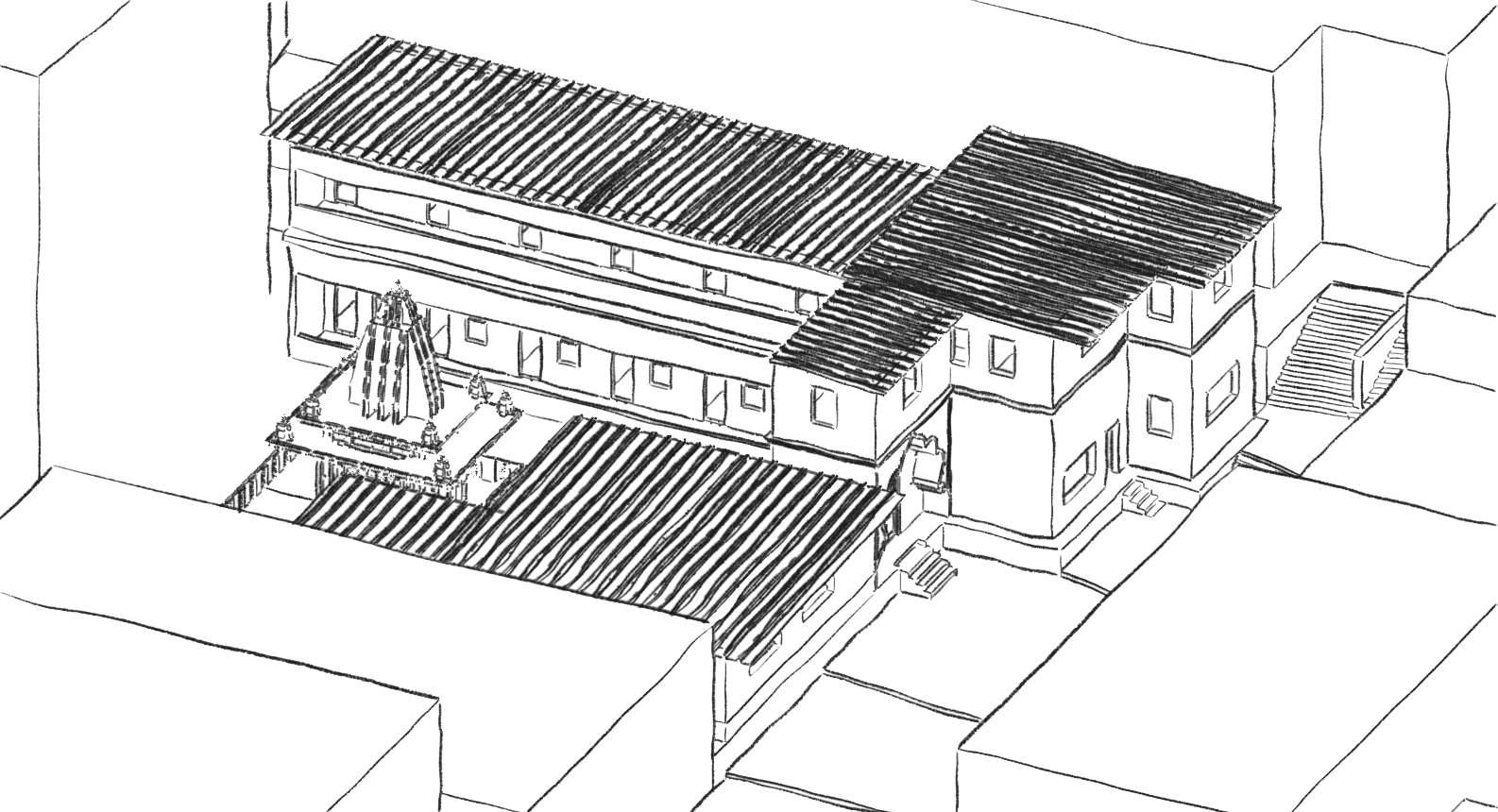

As a student of architecture studying in the northern suburbs of Mumbai city, accessing and engaging with cultural spaces like museums, art galleries or theatres within the city has not only been essential academically, but also of personal interest. For a long time, the geographical distance of these cultural institutions prevented me and my friends from regularly visiting these places since most of these are located away from the northern suburbs, in the far downtown of South Mumbai. From the distant suburbs, these spaces seem to be the primary location of cultural production. Historically, the suburbs of Mumbai grew as the city’s residential backyard - to become a place for recluse for its productive south. However, today, unlike the quiet, aloof and low-energy suburbias (as theorized amply) of the West, suburbs of cities like Mumbai are dense, bustling and thriving neighbourhoods in themselves that have made for themselves spaces for recreation, leisure and rejoicement towards their own needs for the expression and celebration of collective thoughts and identity. Yet, the understanding prevails that suburbs remain culturally bereft neighbourhoods with the city centre being the sole nucleus that generates and houses all cultural activity. The thesis unravels and examines this assumption and redirects its gaze to attend to culture in my “backyard”.

This led me to closely look at Goregaon and Dadar, two neighbourhoods in Mumbai, where I studied a 500 M x 500 M space in each to understand the kinds of cultural infrastructures they house. Some of these spaces seem to be doing a lot more in a lot less space in a suburban neighbourhood that sits as the backyard of the city. These forms of engagements produce distinct typologies of spaces for cultural consumption having unique spatial features. Many versions of these get formed in various infrastructures such as schools/colleges, playgrounds, temples, community(samaj) buildings and act in varied ways working around and taking on institutional logics within themselves.

The studies point to a very different dynamic of cultural infrastructure in the suburban neighbourhoods of Mumbai from the high art infrastructures in South Mumbai. However many of them are still bound to caste, class and gender hierarchies. While they provide clues to more democratic and flexible infrastructures by their sheer access and popularity, one finds that they need a new push to break them from the shackles of societal hierarchies. The thesis asks what new cultural infrastructures could be generated in the suburbs that allow art to become a part of everyday life but to be able to ask fresh questions about life and living.

(Read More)

This led me to closely look at Goregaon and Dadar, two neighbourhoods in Mumbai, where I studied a 500 M x 500 M space in each to understand the kinds of cultural infrastructures they house. Some of these spaces seem to be doing a lot more in a lot less space in a suburban neighbourhood that sits as the backyard of the city. These forms of engagements produce distinct typologies of spaces for cultural consumption having unique spatial features. Many versions of these get formed in various infrastructures such as schools/colleges, playgrounds, temples, community(samaj) buildings and act in varied ways working around and taking on institutional logics within themselves.

The studies point to a very different dynamic of cultural infrastructure in the suburban neighbourhoods of Mumbai from the high art infrastructures in South Mumbai. However many of them are still bound to caste, class and gender hierarchies. While they provide clues to more democratic and flexible infrastructures by their sheer access and popularity, one finds that they need a new push to break them from the shackles of societal hierarchies. The thesis asks what new cultural infrastructures could be generated in the suburbs that allow art to become a part of everyday life but to be able to ask fresh questions about life and living.

(Read More)

06 / Of Screens and Projections

> The Dream House - Sneha Pawar

A home of our own is something that everyone aspires to have one day, a house of our dreams. We all have an idea of it which we imagine, how it should be, where it should be and we work towards achieving that. How do we construct this idea of a dream house? What is it for us? Where does this idea come from? There is a perception of a dream house that is alluded to ownership, a house with a front yard, a backyard, a house close to the sea, with a garden/balcony. Is then the idea of a dream house so monotonous, where every single person consolidates the same idea of a house.

This study revolves around the development and the architectural practices associated with it, aspirations, and dreams of people in the small town of Malegaon in Maharashtra. Life practices and routines of people here become instrumental while conceptualizing the idea of a home. However, the recent development in the housing sector mimics the larger practice of housing as seen in major metro cities like Mumbai, the apartment type. With the notions, beliefs, and aspirations of people here being so diverse, I think it's unfair to impose them with a certain type of housing where this concept of living is still new, finite, and not necessary considering the opportunities.

To explore this notion further I decided to look at what people actually dream of, look at their inner selves, what they actually desire, which happens when they sleep. I looked at nine cases of people living across different class groups and did a detailed interview asking them about their dreams and true them as they spoke about them.

The dream space which they spoke about was different from what their aspirations were. The term dream house which people generally talk about seems to be emerging from the aspirations put together through economic consumptions. However, the actual dreams which are about their desires, strokes, anxieties appear to be absurd, vague, and scaleless. What they spoke about is an aspiration, not the dream because our dreams are the work of our subconscious and they are very intuitive. It is an intense act of reconciliation of all our thoughts, actions, and memories which then reflect back on us. Our dream house/space is something we actually dream of, which is constructed through our thoughts, memories, experiences, fears, and desires.

We from the very beginning inculcate this whimsical idea of an ideal or a luxurious house to be into the greens or into the mountains which we consider to be our dream house. Also because the notion of that place is as such that it should provide us peace, calm, and comfort. But in the hustle, we forget about the other dimension of space that could exist, our dreams. This thesis aims to explore that space of dreams which is different and beyond reality and to bring out the spatiality of the dreams in the real world.

(Read More)

This study revolves around the development and the architectural practices associated with it, aspirations, and dreams of people in the small town of Malegaon in Maharashtra. Life practices and routines of people here become instrumental while conceptualizing the idea of a home. However, the recent development in the housing sector mimics the larger practice of housing as seen in major metro cities like Mumbai, the apartment type. With the notions, beliefs, and aspirations of people here being so diverse, I think it's unfair to impose them with a certain type of housing where this concept of living is still new, finite, and not necessary considering the opportunities.

To explore this notion further I decided to look at what people actually dream of, look at their inner selves, what they actually desire, which happens when they sleep. I looked at nine cases of people living across different class groups and did a detailed interview asking them about their dreams and true them as they spoke about them.

The dream space which they spoke about was different from what their aspirations were. The term dream house which people generally talk about seems to be emerging from the aspirations put together through economic consumptions. However, the actual dreams which are about their desires, strokes, anxieties appear to be absurd, vague, and scaleless. What they spoke about is an aspiration, not the dream because our dreams are the work of our subconscious and they are very intuitive. It is an intense act of reconciliation of all our thoughts, actions, and memories which then reflect back on us. Our dream house/space is something we actually dream of, which is constructed through our thoughts, memories, experiences, fears, and desires.

We from the very beginning inculcate this whimsical idea of an ideal or a luxurious house to be into the greens or into the mountains which we consider to be our dream house. Also because the notion of that place is as such that it should provide us peace, calm, and comfort. But in the hustle, we forget about the other dimension of space that could exist, our dreams. This thesis aims to explore that space of dreams which is different and beyond reality and to bring out the spatiality of the dreams in the real world.

(Read More)

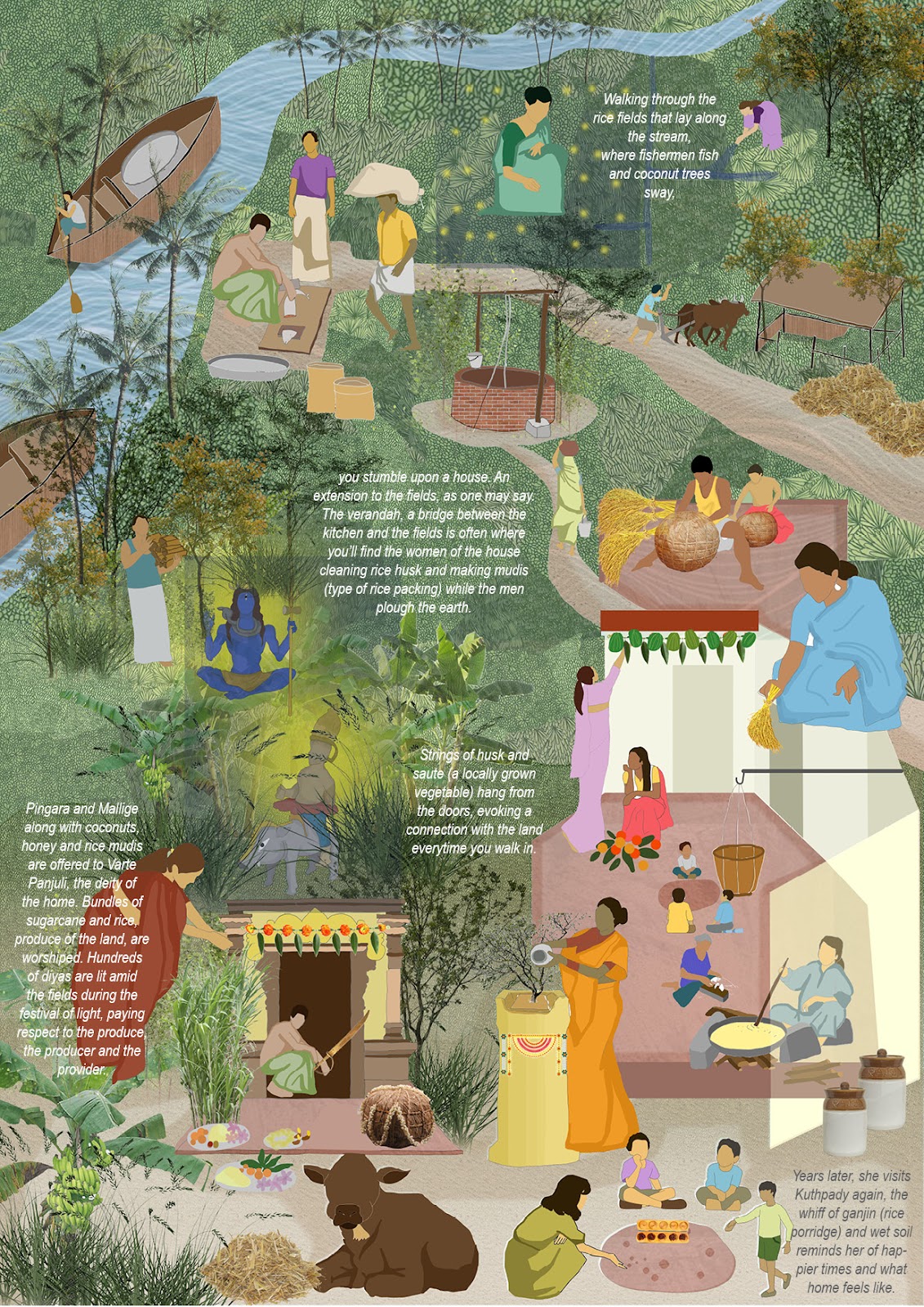

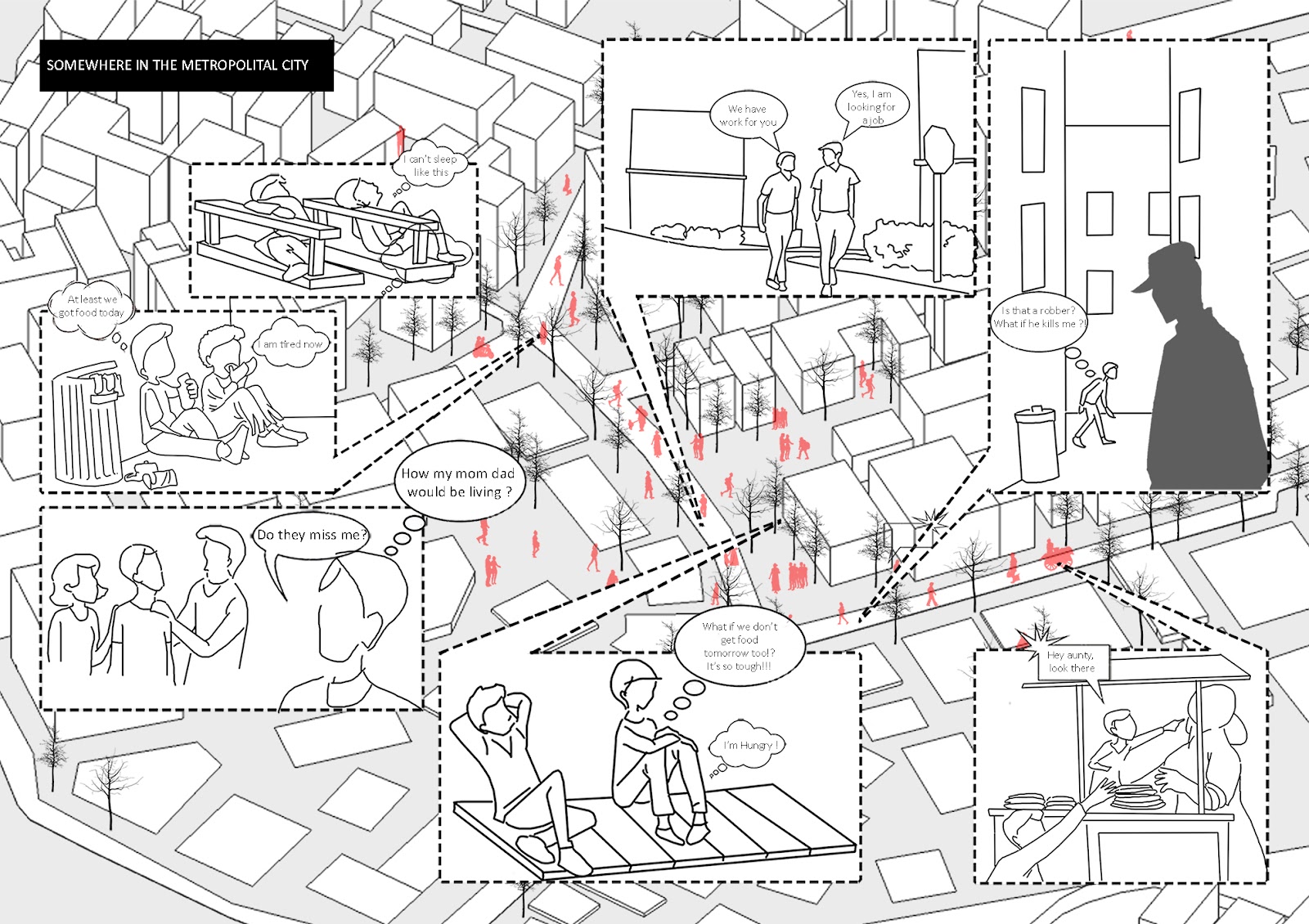

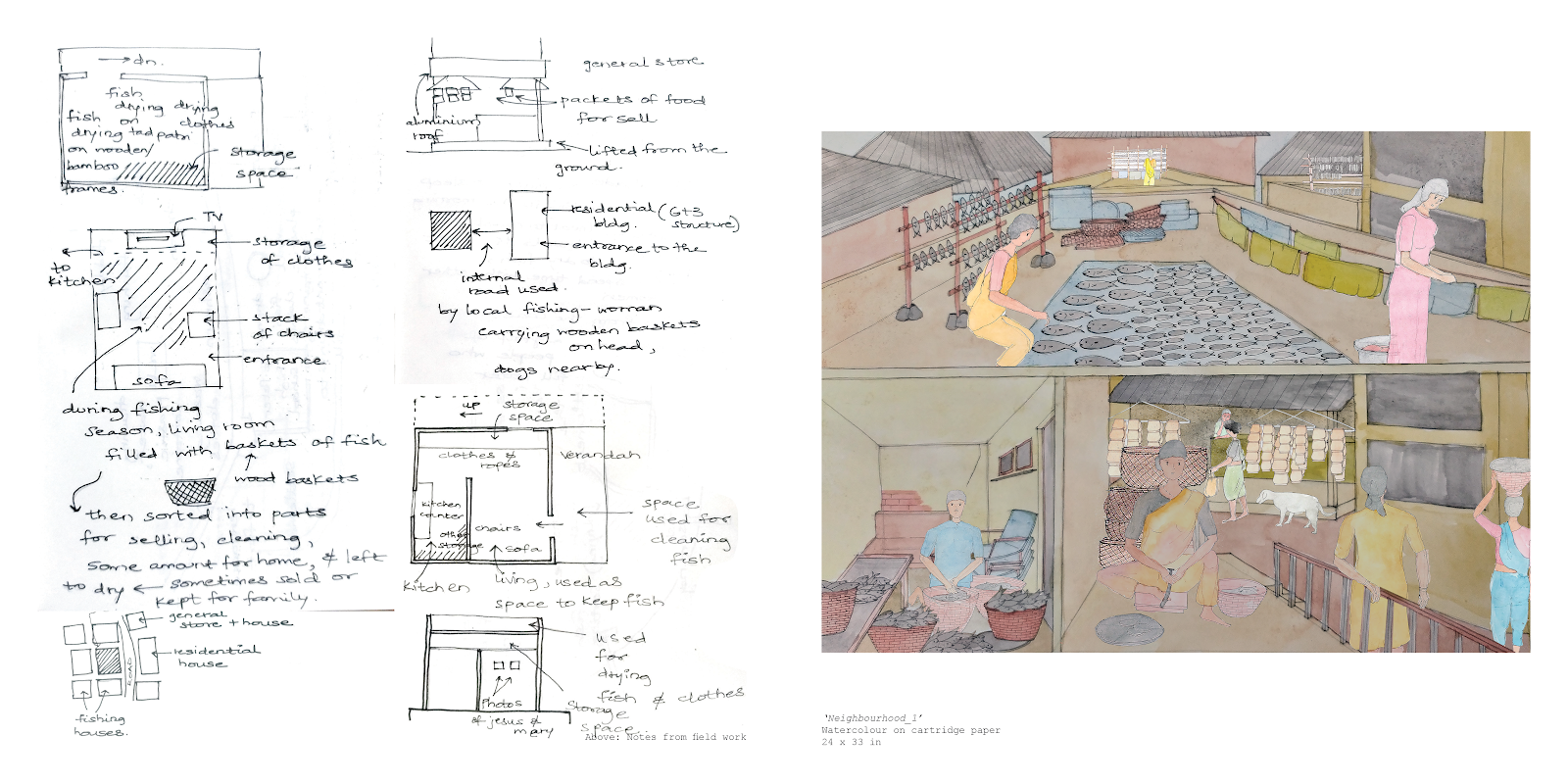

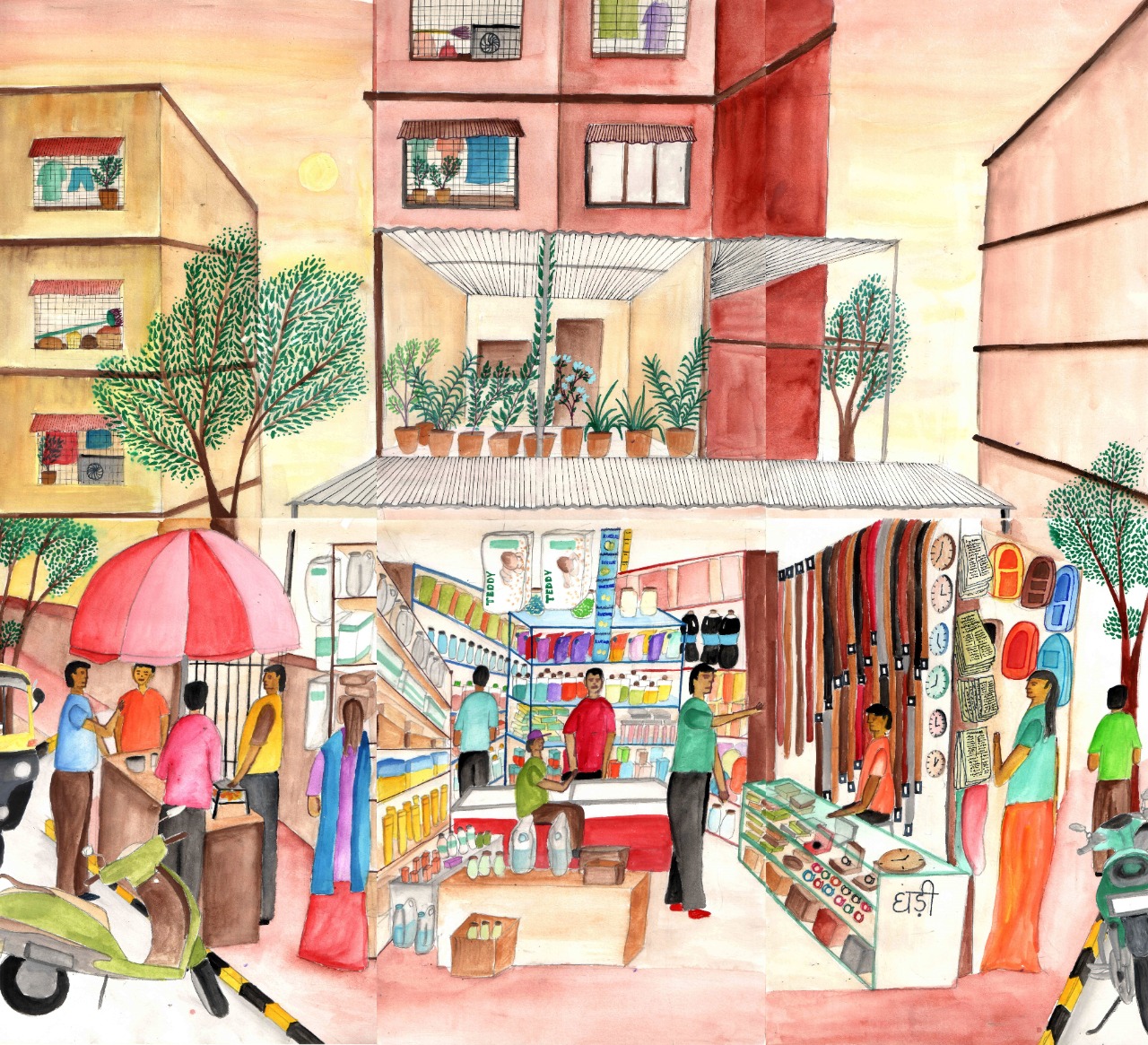

> Cinema Space - Arkdev Bhattacharyya